What do you know about your native language? This question makes many people think about the rules they learned for writing the standard way (like “don’t end sentences with a preposition”), or the history of their language. But what makes someone a fluent native speaker or signer isn’t that sort of book-learning, it’s the implicit knowledge they acquired as a child. The implicit knowledge that tells them what order to put words in, or what sentences seem natural.

How do children acquire this huge store of implicit knowledge about how their native language works? How do they master such a complex, highly-structured system in just a few years? My research explores several different pieces of this puzzle, using different morphosyntactic dependencies, or places where the form or meaning of one word depends on another, to find out what children and adults know, and how they learn it.

Subject-Verb Agreement

Languages indicate the relationships among words in a sentence in two primary ways: word order and morphology. In English, we mostly rely on the order of words to tell us how the sentence works: The cat chases the dogs describes a very different scene than The dogs chase the cat. But order isn’t the only difference between these sentences. As in many languages, in English the form of the verb depends on properties of its subject: chase when the subject is plural, and chases when it’s singular.

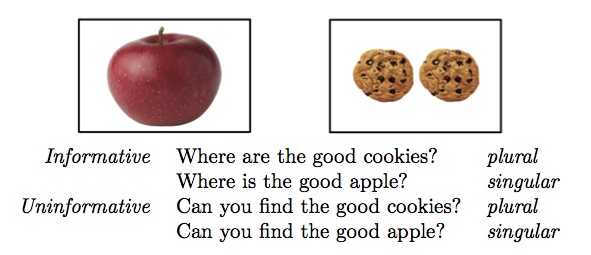

My research on 2- and 3-year-olds’ use of English subject-verb agreement in comprehension shows that even very young children use agreement as a clue about what might be coming up when they are listening to sentences. When children hear Where are the good cookies?, they are quicker to look to the target picture, than when they hear a sentence that doesn’t include is or are as a clue to how many things are being discussed (like Can you find the good cookies?).

My research on 2- and 3-year-olds’ use of English subject-verb agreement in comprehension shows that even very young children use agreement as a clue about what might be coming up when they are listening to sentences. When children hear Where are the good cookies?, they are quicker to look to the target picture, than when they hear a sentence that doesn’t include is or are as a clue to how many things are being discussed (like Can you find the good cookies?).

In other studies, I’ve looked at how preschoolers mark agreement in their own sentences, and at whether adults and preschoolers treat agreement as indicating the grammatical number or the actual number of things they’re talking about. Grammatical number and actual number usually line up (cat, cats), but they don’t always (one pair of glasses, many ears of corn). It looks like, in English at least, the answer is “a little of both”, but there are reasons to think that might not be true in every language.

Another thing I like to think about is the influence of variation on children’s learning and adults’ language processing. In one study, I explored how agreement neutralization, where a seemingly singular verb form appears with a plural noun (like There‘s some cookies in the kitchen), influences real-time comprehension. This pattern usually occurs with ‘s, not is, and is very common in spoken English. Adults seem to know that, and so they don’t trust ‘s to tell them about the number of an upcoming noun, even though they do trust the full is to indicate an upcoming singular. 4- to 6-year-olds are a little more suspicious: They don’t seem to trust any of the singular forms.

This work lets me explore big questions about children’s and adults’ representations of grammatical categories and dependencies, the learning mechanisms children use to acquire their language, and how these things are influenced by naturalistic variation in the input.

Plural Morphology

It’s not just dependencies that variation might influence, but learning the morphology itself. Another set of projects explores how children and adults understand the Spanish plural /-s/ in varieties of Spanish that often leave off or weaken final /-s/. Prior studies have found that variability slows children down as they learn, perhaps because they’re trying to figure out a more complicated system than kids who always hear the /s/. That is, Chilean kindergarteners, who hear /s/ less often, are more likely to give singular responses to plural requests like Pon las botellas en la caja (“Put the bottles in the box”) than Mexican kindergarteners, who hear /s/ more often. However, we also find that at the group-level, Chilean children are sensitive to the plural, and that adults (in Andalusia, where they also drop the /s/) are very good at processing even the less salient, weakened form of the morpheme.

This, combined with other labs’ work showing that English-learning children master the allomorphs of the English plural (the different ways the plural /s/ sounds on cats, dogs and horses) at different ages suggests that there are some very interesting questions to ask about how frequency, salience, and patterns of predictable (English) or structured probabilistic (Spanish) variation influence acquisition.

Negation

A few of my most recent projects explore English sentences with two negative elements (like, The soccer coach didn’t praise nobody at tryouts.). In one project, we’re asking how speakers choose between negative words like nobody and words like anybody in three different varieties of English. To find out, we’re exploring corpora of spoken English, including CORAAL (the Corpus of African American Regional Language) and AAPCAppE (the Audio-Aligned Parsed Corpus of Appalachian English). These are great resources, and we’re very excited to see what we find.

Other projects in this line are exploring how speakers of so-called “standard” or “mainstream” American English, who don’t usually use the nobody versions of sentences like these understand them when they encounter them anyway. We find that they’re pretty good at it! When you ask them outright, they say that they’re not good sentences, but they understand what they mean without a problem, and actually often find them easier to understand than true double negation, where context tells you that the negative elements cancel each other out (like, The soccer coach didn’t praise nobody at tryouts, she praised Kara a couple times.).